Santiago Olmo

3.06.2010

From: Olmo, Santiago. “How to Speak from the Media?” La Promesa de la Política / The Promise of Politics, Edited by Fundación RAC, León, Spain. (illust.) pp. 9 – 29.

ISBN 978-84-614-5421-1

How to Speak from the Media?

by Santiago Olmo

At the end of 2009, when the Rac Foundation and the 31st Pontevedra Biennial decided to start a collaboration which would allow them to join forces and connect their exhibition spaces at the Sixth Building of the Pontevedra Museum and the halls of the Foundation to develop Utropics Project devoted to Central America and the Caribbean, we thought that the most appropriate model would be that of organizing an individual exhibition of an outstanding artist in the region. In the selection process we focused on performances since this is a discipline that not only has had a spectacular development in recent years among the new generations of artists but, especially, because it very eloquently summarizes creative processes and the need of approaching social and political reality from a critical point of view. In Central America and the Caribbean, performances have allowed many artists to codify models of critical resistance by offering a platform connecting them with the audience and with daily problems. Interaction works as a catalyst for change, and together with a participation framework and even collective catharsis, underlining the conditions of community self-awareness in the absence of an effective and articulated civil society, are among the elements on which the social and discursive importance of performance in these contexts is based.

It is true that differences between various countries, due to political situation and history, as well as the diversity in the development of their art scene, give rise to accentuated specificities. What allows approaching the performance phenomenon as a general symptom of revolt and hopes of change is the way in which reality is faced through the body (of the artists) from a situationist perspective gliding to an understanding (also psychologically based) of the causes of social problems.

Performance, in contrast to painting, photography or sculpture, has a larger capacity to create a climate intended to raise public awareness and, therefore, to influence reality and its transformation. Thus, staging the action (with participation mechanisms shared by the audience) may produce in spectators, whether individually or collectively, a psychological catharsis that shows the way to raise awareness. In this sense, just as happens in theater, performance acquires a pedagogical meaning which is intimately linked to psychological inner experience.

It is not mere chance, then, that when thinking in a performance for the Rac Foundation we chose Tania Bruguera who in recent years has developed an extremely consistent corpus of works and is one of the most outstanding artists in the international scene.

Tania Bruguera’s project, under the title The Promise of Politics, is closely linked to the section Archivacción (Archivaction), part of the Utrópicos (Utropics) exhibition in the Biennial at the Sixth Building of the Pontevedra Museum, with an appliance created by Galician artist Carme Nogueira which includes a file of various performances by 18 artists from Central America and the Caribbean and offers video documentation of several versions of Tania Bruguera’s project Tatlin’s Whispers #5 at Tate Modern in London, # 6 at Valencia’s IVAM and #6 at the Tenth Havana Biennial.

The Promise of Politics is a project divided into five performances based on news released by various Spanish media during 2009 and 2010. The presentation has an exhibition format together with simultaneous actions with a trace maintaining a strong sculptural nature linked to a rather reconstructive view of what is “monumental.”

In Tania Bruguera’s work there is a remarkable fluctuation between ephemeral action, which is the nerve of action in performance, remains and the trace of the action as the scene of the crime transformed into a sculptural anti-monument.

A comprehensive framework, linked through metaphor and, more incisively, through the analogical use of symbols, deconstructed appropriations or staging, plays a decisive part in this unusual and subtle glide. In comparison with other more succinct and minimalist performance projects, her way of working shows a subtle use of procedures whose roots should be found in baroque dramatization, in emblems and iconographies reconstructing the present from the memory of recent history. Then she builds an action platform which has as a purpose articulating actions based on a way of thinking with politics as a starting point. Therefore, just as in the Baroque, it is a symbolic art with a strong political contents tending to liberate the energies contained in prevailing discourses.

Helaine Posner states that “her work examines fundamental issues of power and vulnerability in connection with the individual and collective body politic.”1Her purpose is to create the conditions for a political art influencing behaviors and specific situations and, to that end, use mechanisms unleashing strong psychological emotions in an audience which turns them into characters and actors or actresses and, in short, into the persons implementing the action.

In her early days as an artist, Tania Bruguera made use of quotations when speaking about identity and its contradictions, focusing on its conditions in Cuban contemporary culture. References to Ana Mendieta (Homenaje a AnaMendieta – Tribute to Ana Mendieta, 1985-1996) or Juan Francisco Elso (Destierro – Displacement, 1998-1999) will be simultaneous with the mediation of her own body as a vehicle for an action and a time. However, towards the final years of the ‘90s many of her performances became a mixture between performance, interactive installation and elements with a sculptural-anti-monumental nature. Some pairs of concepts will articulate as emotion and sensation unchaining levers: when vibrating among them these principles allow the liberation of ideas and statements that enrich performances by depriving them of their univocal time and action meaning. In her hands, performances will tend to become a platform and a stage, an object materializing a will of political resistance: to show / learn, evocate / remind, experience / transmit, fear / resistance…

Tania Bruguera’s most recent performances are like programmed plans in which, with accurate instructions as a starting point, voluntaries or hired people will develop situations. More than a dramatized recreation, the program will allow repetitions and constantly review the versions enriched by the performers. In this sense, it is fundamentally a daily activation of transgressions bringing about first raise awareness and then a change: in a way it is like the peaceful implementation of programmed civil disobedience techniques.

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 was held in 2008 in the large turbine hall of Tate Modern in London, with two mounted policemen forcing the audience to remain in some given spaces or to change their site. The action reproduced power relations between policemen and people in the streets during demonstrations or protests, but inside a museum. Options for the audience were few and, especially, passive. The situation changed radically in #6 versions held at the hall in Valencia’s IVAM in 2008 and in the patio in the Wifredo Lam Center during the Havana Tenth Biennial. In both cases, a dais with mikes, where people could go and give vent to their opinions or ideas, was put at the disposal of the audience. While in Valencia the dais was simple – just as the one those in charge of welcoming the audience use –, inthe Havana version the dais boasted a careful revolutionary scenography: an ocher/golden backdrop and a podium with two microphones where actors dressed in olive green meticulously limited the one minute allotted to each speaker and placed on their shoulder a white dove, in evocation of one of the first speeches of Fidel in Havana after the triumph of the Revolution, when a white dove alighted on his shoulder.2In these cases, the performance was activated as a platform for social participation in which work and artist are a means allowing and permitting the action and the awareness raising of the group and of society.

On February 2010, Phronesis followed this pattern at the Juana de Aizpuru Gallery in Madrid. The project was a file of performances which would be held in prestigious art institutions throughout the period of the Madrid exhibition, although they would not be duly authorized. Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 7 p.m. there would be an action in every predetermined place and, once documented, pictures and texts would be sent to the gallery to be exhibited in the walls of the hall, so each work would be completed as the various actions took place. The purpose of the piece was to stress the difference between the notions of citizenship and audience.

Another piece in that exhibition, Revolución provisional (Impermanent Revolution), invited the audience to choose a political slogan and materialize it in a physical experience, by means of a tattoo.

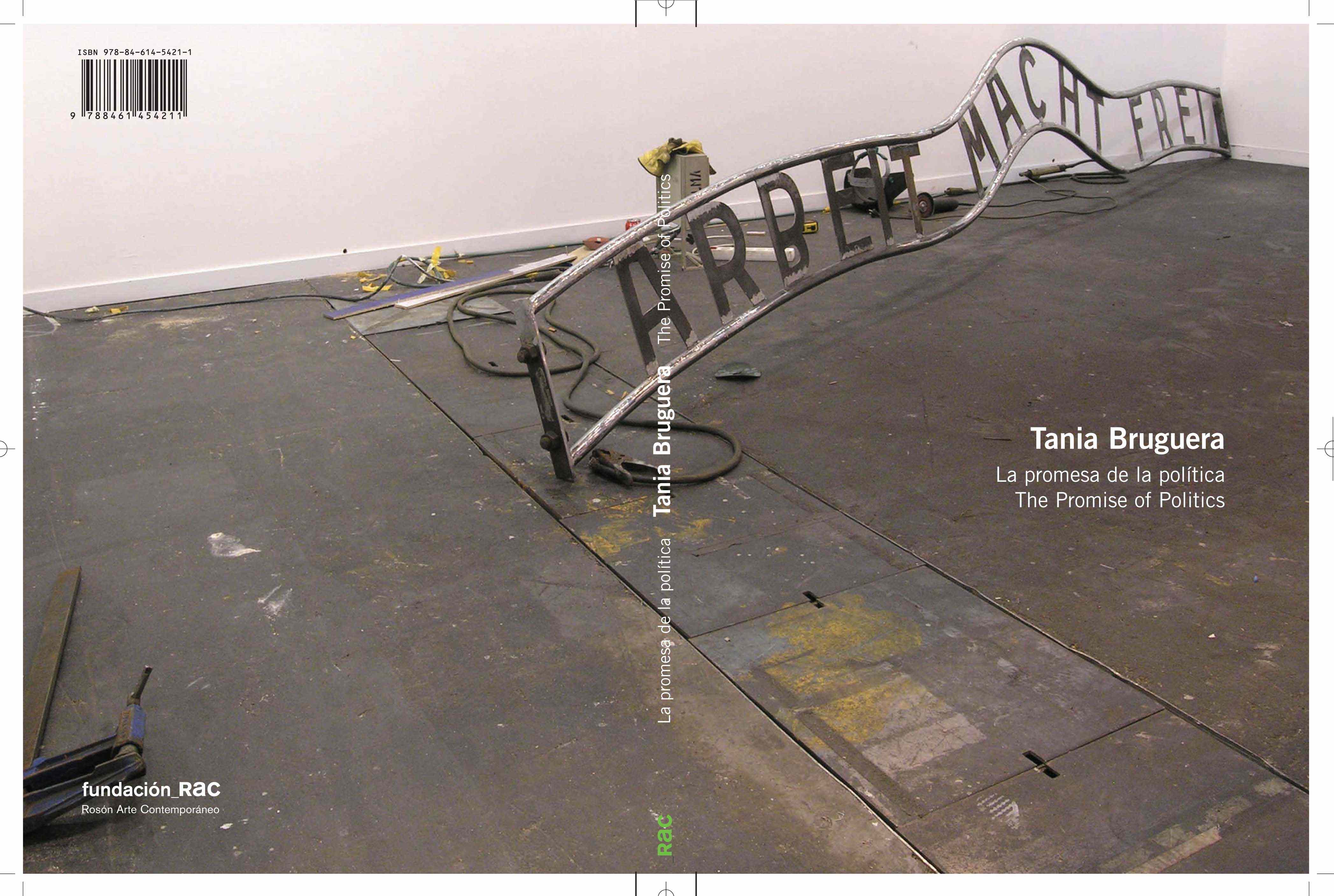

The audience and liberated actors/voluntaries activate the performance, while Plusvalía (Surplus Value), screened in an ARCO Project Room and in the exhibition in the Juana de Aizpuru Gallery itself and part of Rac Foundation The Political Promise, marks the beginning of a series of works inspired in news released by the media and gliding to the above-mentioned sculptural level with theatrical traces. Surplus Value begins with the piece of news published on December 2009 by the press on the theft of the metal sign at the entrance to the Auschwitz concentration camp – now a museum to the memory of the holocaust, with the well-known words “Arbeit Macht Frei” (Work Makes You Free) which has become the emblem of Nazi cynicism – by a criminal gang with the purpose of selling it in the black market for historic and antique gadgets. The Polish police found the sign hidden and divided into three parts. Successive information pointed out that the robbery had been commissioned and the agreed price was 150000 euros.

Surplus Value is a sculptural work part of Political Promise whose activation includes the intervention of the audience which may change the appearance and finishing of the sign by working with the aid of an electric sander.

Over and above the political and historical symbolism of the words in the sign, the mechanism to activate the piece is based on the twists and turns of the demand and offer market as well as on the surplus value of an object that is not the reproduction of the original (understood as a historical document: Auschwitz is today a museum with more than a million visitors per year), but a reproduction of the stolen object. Surplus value, that is, the profit the entrepreneur obtains by taking the benefit produced by workers with their work, is in this case the appropriation of the participating and “festive” action of the audience reverted into the art market: the value of the piece benefits from the audience’s action activating the piece. But also the work shows how a historical-political slogan turns into an object which may be entered into the black and capricious market of rarities and curiosities and, at the same time, into the art market as a work summarizing in the sham of the stolen object a reflection on politics, the market, history and economy.

Nothing is today outside the market and, on the other hand, what is not in the mass media does not exist. The existence of the work has more to do with the news of the robbery appearing in the media than with the robbery as an event in itself.

The universe of news created by the media tends to be confused with reality, or rather merges with it. It is a system implying first of all information processes and these determine the forms in which we perceive and come to terms with the world. When replacing information by knowledge, anecdotes shape up a system of topics allowing perception based on recognition as its starting point. Information, for its part, structures visibility codes which consecrate identity on the basis of ruled singularities.

Recognition is precisely the cognitive system used by tourism and closely linked with the communication system in the media.

The place of imagination and fantasy is inscribed in the succession of news: reality contains what is amazing and it is not necessary to tell it. The media simply make it visible and present their instauration as a closed model.

The news system implemented by the mass media may be summarized as an abbreviated and camouflaged formulation of hegemonic political discourses mostly presented as an apparently innocent succession of information. If, on the one hand, the absence, or even better, the reduction and minimization of analysis, comments and articulated opinion, intends to safeguard a non-viable and impossible objectivity leaving the news in the pristine nakedness of neutral information, on the other it propitiates the dismantling of every system of knowledge leading to the emancipation of the communication mechanism itself.

Politics, trapped in the media system (surveys, evaluations, opinions, comments, visibility, and so on), cannot make freedom act as a mechanism shared by everyone when sharing time and a debate.

Knowledge is what makes us free, while work makes us slaves, as all totalitarian systems, from Nazism and Stalinism to financial capitalism, have intended. But knowledge in itself is not enough to guarantee this liberating emancipation. It is not enough to know the systems of serfdom in which the media system encloses us to neutralize it, although this awareness of enclosure may be a first step in the restoration of a policy of freedom.

When in Political Promise Tania Bruguera shows, through action metaphors, the symbolic representation of five pieces of news released by the press, her purpose is not so much to comment on the media system but to approach, from an apparently innocent piece of news, the political discourses inscribed as a leveling with ignorance on its basis.

It is not the first time Tania Bruguera approaches the news released by the press. In 1993, with the collaboration of several Cuban artist and critics, she created and directed a publication entitled Memoria de la Postguerra (Memory of the Postwar) which included articles on art, culture and literature with the graphic style of a newspaper and gave voice to criticism normally silenced in Cuba by the official censorship apparatus. It was not to be published periodically and only three numbers were made. The second was in 1994 focusing on exile and migration and the third in 2003, now without name or date, only included political slogans of the Cuban Revolution.

Each of the pieces in the exhibition bears the title of a concept appearing in Hanna Arendt’s book The Promise of Politics, which is also the name of the exhibition. Arendt’s book, compiling a series of texts that were meant to be published as a book but were finally used as lose fragments in lectures and courses, deals with the difficult historical relationship between philosophy and politics. The early moment of Greek philosophy, the foundation of Rome as a civil society, the moment of Forgiveness established by Christianity, are all moments of present experience and rupture with the past, together with the analysis of persuasion, truth and opinion, are the nerve of the book and define politics as a space of relationship and outlining freedom as its promise. Freedom should be the area of politics, but not a freedom that only emancipates from oppression, but a freedom in which what is being done allows an escape from the coercions of need.

From Hannah Arendt’s story line, taking pieces of news published in journals as a starting point to transmute them into philosophical concepts should not be considered an intellectual pirouette, but a symbolic procedure updating a discourse on politics and the media to establish action modalities in the emancipating line of a different idea of freedom. In this sense, performances could be understood as a path of experience capable of creating anew a type of knowledge free from the anecdotic burden of information: to rescue the elements of truth from opinion and establish a shared critical space.

But Arendt is only a reflexive starting point, not a guideline, and her purpose is much less the illustration of her thought, which, on the other hand, is something utterly impossible. It is a starting point from ethics grinding the stories of every piece of news to turn them into cathartic metaphors of a political action in a social and civil reflection sense.

Isonomy, that is, equality before the law of distribution implying the equality of civil and political rights of the citizens is the title of a cloth poster where the following text is embroidered:

“Nobody knows the past awaiting him.

Signed: The Management.”

The sentence has to do with the way the past is rewritten to extol or degrade the present. Cuban folk thinking and knowledge that stems from authoritarianism, where truth is irrelevant. Appearances prevail, while social and political relations are established on the basis of expediency or cynicism and directors arbitrarily exercise an order that distorts any possible notion of isonomy.

In the piece of news which Tania Bruguera uses as an example, authority and direction are exercised by a group of drug traffickers, “the Fat Clan,” arrested by the police in their very well organized quarters in Valdemingómez ravine in Madrid.

The piece of news published in El Pais on February 25, 2010 is somewhere between absurdity and delirium in the reproduction of corporative authority systems in the framework of illegality:

“The performance by the traffickers began at the outward-facing door where three men of the clan controlled those who came in or out. Other six guarded the inner doors of the building, some others took care of the sale point and the women, who were the ones who sold and packed the drugs. The main room had closed-circuit TV with six cameras they could see at a near-by room. In the living room, where two women waited behind a counter, there were metal posts with ribbons for consumers to queue orderly, ‘as in airports,’ according to the head of Fourth Group of the UDYCO. The collection was kept in a wicker basket. When it was full, bills were put in a safe with a crack made on top as in a moneybox.

Some rooms had been fitted out for drug consumption and this was indicated in posters pasted on the walls reading: ‘Smokers Area.’ To keep the point of sale open 24 hours, the clan had three eight-hour shifts. On the table where buying took place, there was a poster with the rules the ‘workers’ in the shifts should follow signed by ‘The Management.’”

Isasthein, meaning, do the same, illustrates the collapse of the hero ideal established by the Cuban Revolution with the death or Orlando Zapata in a hunger strike. The piece of news in El Mundo on February 24, 2010, summarizes:

“Zapata was part of a group of 75 dissidents who were condemned in the spring of 2003 to up to 28 years in jail although in his case the accumulation of penalties for “disobedience, defiance and protests in favor of human rights” rose the figure to 36 years in prison. The dissident started a hunger strike when the government did not accept his demands, among them, to dress in the dissident white clothes and not the uniform of a common prisoner. He also protested against the conditions in which political prisoners were kept and did not eat the food provided in jail but only what his mother brought him to prison every three months.”

The day of the opening, a sculptor modeled in clay the bust of the visitors who would pose for a few minutes. When the next model was before him, the sculptor erased the portrait and used the same clay for the next one. The last dry and deteriorated portrait was kept in the exhibition.

Nonsense as that of dying in a hunger strike in a country where the man in the street is compelled to buy his food in what is there called “ the black bag” (black market) and where the lack of essential items is all too frequent converge in Zapata’s drama.

The hagiographic bust of the hero becomes a disposable model, while everyone may become a hero.

Among all the works in this project, Doxa (Greek for opinion) is the most sculptural of all with a poetic metaphor based on an object. In Tania Bruguera’s oeuvre, this type of works may be considered exceptional, but evidently putting a distance between the actions by the body itself and intervention itself opens the way for vestiges of the idea to materialize and come into being in the same level as objects. This path is parallel to that she started some years ago, that of taking performance to the status of artistic merchandise. Tania Bruguera is one of the performance artists who have been most concerned with changing the status of performance in the market. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, performances tended towards an extreme dematerialization and the status of a work inscribed in a fixed and unrepeatable time; in the 2000s, performance tends, not only through versions, to extend in time and to dialogue with contexts (something which allows performances to overcome their nature as eminently specific works and become works adapted as theater plays). For example, Tatlin’s Whisper #5 was bought by Tate and it was the museum which commissioned the work for its turbine hall.

But let us go back to Doxa. The piece has no performance quality: a white egg on a pedestal resists in its whiteness the blaze of a blowtorch because of the distance separating them. Only one centimeter nearer, the blaze of the blowtorch would burn the eggshell blackening it.

The open nature of the work might give rise to many interpretations and analogies based on its poetic qualities. Adhering to the title itself, Doxa (opinion), and establishing its classic antagonistic link in Greek philosophy with truth, it seems to reopen that baroque drive for symbolic emblem and iconography we have earlier mentioned. As in the baroque, emblems are at times contradictory and confusing, but in one or other sense they function as the expression of a thought tending to show the reality with images as their point of departure:

A) The egg representing the truth is permanently threatened by the insidious

blaze of opinion.

B) The blaze of truth hovers over the topical images of opinion (the egg) to

disclose their fragility and falseness

Perhaps what distances Tania Bruguera from the baroque is her extreme minimalism, the absence of a “poetic program” characteristic in emblematic objects, avoiding giving too many explanations and sorting intellectualist abstraction. Her attitude is that of addressing attention directly to the nerve of the problems, to the nucleus of situations, with no detours.

The piece of news which is the cause of this piece of work is a communiqué from the Japanese royal house informing of the harassment at school of nine-year-old princess Aiko by a group of schoolmates in the upper grades. The unhealthy curiosity of the piece of news shows not only the extent of harassment and mobbing, but also – and journalistic comments speak at length of this, in the March 5, 2010 article in El País, for example – on the deep sadness the princesses in the Japanese court suffer:

“Aiko is the only daughter of Naruhito and his wife, Princess Masako, who has suffered for years from depression induced by stress which has won her the name of ‘the sad princess.’ Many blame her depression on the rigidity of the protocol in the Imperial House and the strong pressures she has endured to bear a son that would perpetuate the Japanese imperial line. Succession Law in Japan establishes that only a man may be emperor, which prevents Aiko to inherit the Chrysanthemum Throne. Next in the succession line is three-year old Prince Hisahito, the third son of Naruhito’s younger brother, Prince Akishino, and his wife, Princess Kiko.”

The ritualized life in court becomes a golden cage where rules that do not fit modern life prevail and the position of women in this system takes on the status of ill-treatment, at least in psychological terms. This unusual scene is far from the false image spread for decades by true-romance magazines, based on romantic legends on royalty and feeding on it. The myth young Sissi was in the Vienna court is perhaps the one that best summarizes the collective imaginary of the happiness of a royal couple and the misfortune and curse leading to a tragic end: stabbed by an Italian anarchist while taking a walk down the shores of Leman Lake in Geneva. Sissi’s happy and tragic “story” has been transmitted to the modern popular imaginary through films and, oddly enough, her figure embodied by Romy Schneider contributes to the feeling of tragedy in the dramatic life of the actress.

Peithein, persuasion in Greek. In Greek mythology, Peito, the daughter of Hermes and Aphrodite, embodies seduction and persuasion. This is the title of the fifth work in the exhibition in which a young man on a scaffolding is painting a white wall white. When entering the hall from a higher floor, spectators see the painter working. Nothing seems unusual. A more attentive and closer look reveals that the worker has his fly open and is discreetly showing his penis.

In literary and popular imaginary, from Boccaccio’s Decameron to D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover or, more recently, in urban legends consecrated by burlesque films and comedies of manners, there are innumerable scenes in which mule drivers, grooms, gardeners or butane gas deliverers, seduce the lady in house or are seduced by her. Besides, in the Decameron there are abundant stories and scenes of lustful priests and clergymen seducing young and not so young ladies. But it is in 19th century novels where the psychological background of the persuasive and besieging seduction of the Don Juan wearing a cassock, the confessor, is more explicitly stated. Stendhal’s The Red and the Black or Clarin’s La Regenta (The Professor’s Wife) are the summits of an almost picaresque genre that dates back to the Middle Ages and sinks its roots in the problem of celibacy for the Catholic priesthood. Protestantism and, before, the Eastern Greek Orthodox Church, partially solved the problem of celibacy with the possibility of the protestant pastor forming a family, while the orthodox church may order married men with women of good reputation, but the topic of seduction continues open. The seduction of a girl by a pope is a topic not too frequent, but at least curious and reiterative in 19th century Russian painting and, in Fanny and Alexander, Ingmar Bergman recounts the relentless pursue of a widow, the mother of the children in the title of the film, by a strict pastor wanting to marry her.

The image of the priest and of religious authority in general is not univocal, but has many folds and it tinted (for representatives of all denominations) with a rigor verging on cynicism and hypocrisy, especially in matters touching sexuality and the body. It undoubtedly is the symbolic tax which the innocent pay for the guilty in a literary and oral tradition of stories in which seduction takes place from positions of authority and through persuasion.

The news at the origin of Peithein was published in Público on February 24, 2010, on the bizarre and cybernetic cynicism of a priest in two small localities in Toledo who used the money of the church to announce himself in Internet offering sexual services. The tone of the piece is really something and exceeds any comedy of manners in satiric cinema:

“Heterosexual man for women and couples. In Toledo. Real stills. Well-hung (15 cm) for your pleasure and happiness. 15 minutes: 50 euros, 30 minutes: 75 euros and one hour: 120 euros. I am open to everything except sado. You will not regret it. I will make you enjoy happiness as never before.”

With these words and two pictures, one dressed and the other half-naked, Samuel Martín Martín, a 27 year old parish priest from Totanes and Noez, two localities in Toledo with a population of less than 700 among them both, announces his sexual services in Internet. Apart from selling his body in the Net, Martín allegedly stole 17000 euros from the brotherhoods in the municipalities and spent them in erotic telephone lines and pornographic services paid through Internet. Not satisfied with that, he allegedly intended to sell a painting of Saint Jerome from the church in Noez. The advertisement had the following text: “Canvas painting from the 17th century, unknown author, but belonging to the school of some important painter of the times. Negotiable price.”

The media system incessantly offers an ever more variegated and anecdotic casuistry. A reconsideration of politics as a platform for social encounter could update the promise of freedom Hannah Arendt assigns to politics.

How can performance intervene in this always fragile construction?

1 HelainePosner, “Introducción a la publicación Tania Bruguera”. On the political imaginary, (Milano: Ed Charta, 2009), p. 15.