Yolanda Wood

July – September 2000

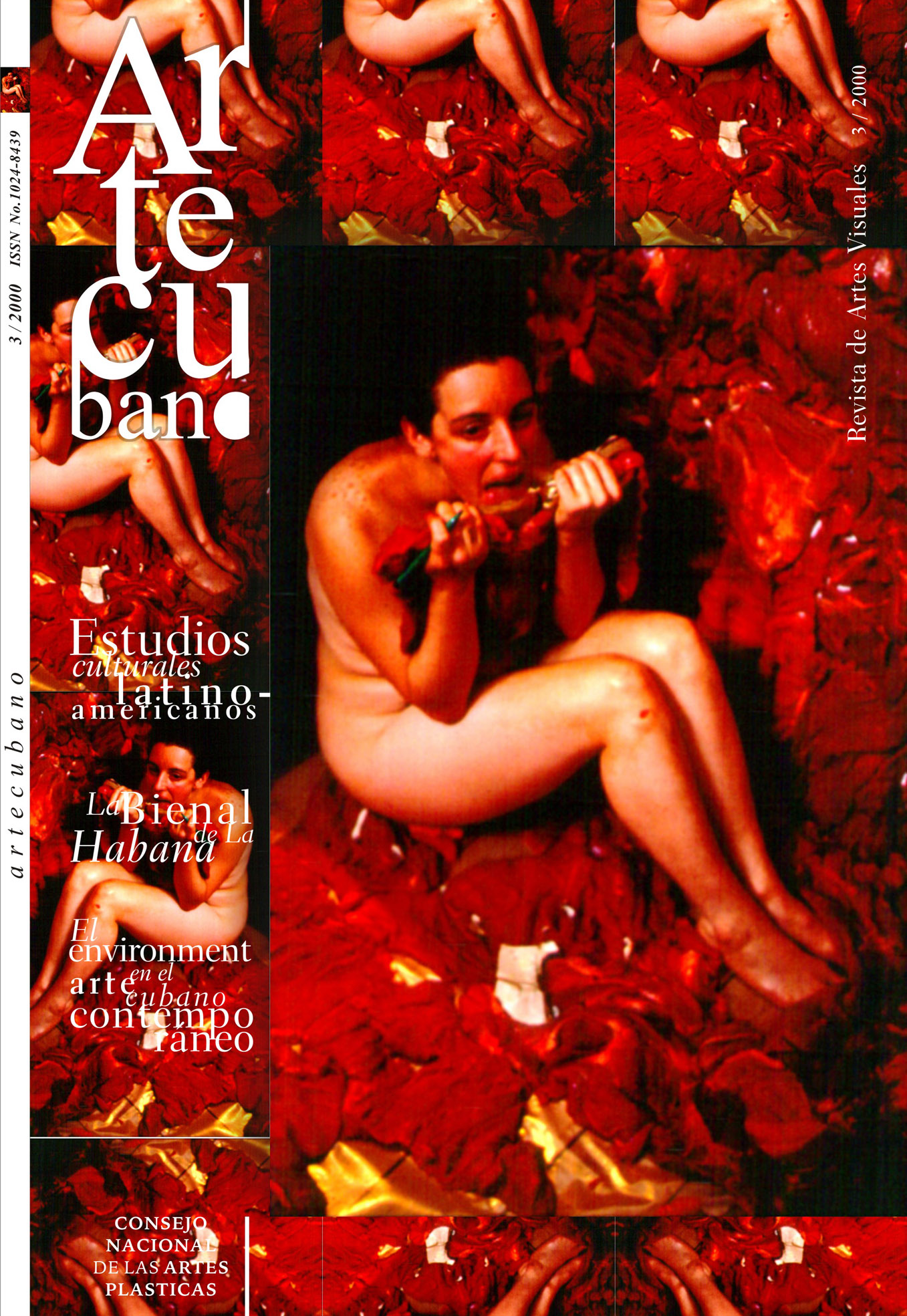

From: Wood, Yolanda. “La aventura del silencio en Tania Bruguera,” Arte Cubano, no.3, Havana, Cuba, 2000, (cover & illust.) pp. 34 – 37.

The Adventure of Silence in Tania Bruguera

by Yolanda Wood

And even silence says something,

since it is pregnant with signs.

Octavio Paz

In the intense Cuban visual arts panorama of the ’90s, Tania Bruguera’s work is loaded with an evident originality because of having identified her individual way of doing performances. While art traveled through diverse searches and experiences, Tania’s always tended to explore the intense relationship of the artist and its audience through non-traditional means and ephemeral works. This identifies her with a poetic in which multiple resources converge; among them – she has told me – “silence is fundamental,”1 which seems to contradict all attempts at communication. And it is that Tania resorts to the concentration and solitude silence propitiates as a means to strengthen communication. In this inner silence of her works all the questions and all the answers seem to be contained. It could also be said that none of them are and it is in this ambiguity where the adventure she herself plays in each of her pieces starts.

The subject of the work is always Tania, who expresses herself with her own body, in a conspiratorial relationship with herself, thus creating a first area of essential silence that pollutes the entire work and turns it onto a moment of liberation for the artist through a splitting process which is her alter ego, her other I, which Tania identifies as energy: “Before I do the work I sit by myself, calmly, to visualize what is going to happen. The piece must run before me as a film.” It has to do with achieving the concentration and relaxation that will contribute to liberate instincts and will give authenticity to the process in the moment of its public presentation. It has to do with creating an interface between the artist and the subject of the work, in which the entire conceptual basis of the piece must move from a rational to a sensorial existence in which everything that she has thought is incorporated into an instinctive procedure.

“That is why I don’t practice the work,” the author has told me. “I need that moment to be magic. That is when I feel well: it is the moment in which all the parts of my body fit perfectly. Then ecstasy arrives.” Perhaps that is why Tania insists in saying that her works do not exhaust her physically, although she may have to adopt uncomfortable poses or carry out acts of difficult contraction for a long time. In this complex process, she always tries to find a new surprise and to avoid all mechanistic elements.

Of course, like every connoisseur may understand, we are speaking of works chronologically between 1994 and the end of the century in which the author undergoes increasingly complex situations… we may say limit situations expressed as a rhetoric of obsessions. Tania’s work may inspire in researchers an entire critical search from the point of view of art psychology. “There are obsessions in my work and they are conscious; silence is one of them, and so is repetition.”

Whomever has observed Tania’s performances will notice that the entire design of circumstances places the subject in extreme conditions, where the individual seems to be at the point of madness, this understood as the most critical and decisive moment of an event. Then “I choose a gesture and repeat it infinitely… continuous movement is something without beginning or end.” Tania build the catharsis and reconstructs it with contractive, simple, introspective gestures, directed towards exorcism within the forms of a primitive rituality, as happens in the series El peso de la culpa (The Weight of Blame). In it, everything refers to a reverse spiral movement. In Estudio de taller (Workshop Study), a work with much impact on the audience at the Sao Paulo Biennial, the immobility demands imposed by the circumstances of being tied, bent and holding for a long time a beating heart in her hands (which could very well be hers because there were blood stains on the left side of her breast), may explain this understanding of art as an exercise of self-controlled energies in limit situations.

In this sense, the subject in Tania’s work is an explorer of agonizing feelings, seen more from the point of view of what is transcendental than from what is circumstantial. That is why the pieces settle in a humanistic discourse beyond dailiness since, according to what the author has said to me, “in a cultural level, references are lost” and this is perhaps what allows the dialogue of the works with audiences from different places. I actually believe that what happens is the transference of perceptive experiences that the audience contextualizes on the basis of its own cultural references. “When they are before the pieces, they see and feel their own agonies and perhaps feel agony because they do not understand that of the other being and this has a function too.” In this sense, Tania’s work upholds provocation strategies in the aesthetic-cultural level.

Tania Bruguera’s résumé testifies to her condition as an artist positioned in the most important circles of international art. In Latin American countries, as well as in Europe and the United States, her work has been acknowledged and its worth is well established. Undoubtedly, it is that humanistic dimension that guarantees its transcendence, although international criticism has rather tended to relate Tania’s work with an island political circumstance which trims down its meaningful values. If the Cuban context defines Tania’s work, it does it more from the social perspective in the difficult years of the “special period” when, after the fall of the socialist field in the ’90s, national economy dropped to unforeseeable indices and supply cutbacks, programmed electricity cuts and the conflicts stemming from the resistance to adversities made its impact be felt in every Cuban home.

The most important topics in Tania’s work have to do with emigration and with the conflicts of subjects in extreme conditions. It might be considered that the obsessions of the hard years in Cuban economy and society left a visible mark Tania Bruguera’s work. Since thematically her pieces are positioned in the extremes, however, if we understand agony from the Greek etymology of the word (fight and combat), the most generalized situation of Cuban society is blurred. In Tania’s work, emigration is an escape way in dangerous conditions; the artifacts she builds are revealed as a fruitless possibility and a state that seems to precede death, as happens in the series Dédalo o el imperio de la salvación (Daedalus or the Empire of Salvation). It is also a skeptical and passive behavior in which discouragement at the adverse conditions imposed by survival settled. In this dichotomy the artist reveals two models of critical and polarized psychosocial attitudes, the first one conditioned by the hostility of an “adjustment” law2 which favors her; the second, because of the “disarrangements” generated by states of crisis. From a thematic point of view, Tania’s work goes to the extremes which – as the wise popular saying runs – touch each other. This sets her apart from all contextual verisimilitude and it is precisely in that interpretative dynamics that the work functions like a universal dilemma.

Tania’s work is entirely alien to any representational meaning, which is why it functions symbolically at a tropological level. This perhaps has to do with the effect the artist is interested in: removing and moving the spectators’ awareness. Tania has the keys to do it on the bases of her conceptual training during long years studying art in Cuba and abroad. That is why she herself, as the subject of her works, says the splitting she practices is more of awareness than of personality. “I am not interested in acting. I do not play characters.” It is rather a process which liberates instincts displacing the individual in its objective rationality to place it before a space of sensorial confrontation with itself. It is an exercise in exorcism which, more than reflecting a circumstance, indicates a regenerative function of art as a communication channel through which the artist and its alter ego atone for all their blames. In this sense, Tania’s work does not escape its own contacts. “I cannot separate my despair in art from my individual one to get to be the person I want to be with the contradictions we all can have with the world surrounding us.” In artistic terms, she is weighed down by pigeonholing… in this sense “I do not now say I make performances. That word upsets me. It upsets me that it is in English. I am a visual artist.”

Also, the artist rejects any classification of her work from a gender perspective, which seems unavoidable because of the artist’s sex and that of her alter ego: “I am a woman… that is my nature; why is it that when men make art it is universal and women are marked with an identity seal of gender?” The fact that in her more recent works she appears entirely naked, however, makes one think in a generic intention although it is essentially characterized by a type of opaque sex. It could be said that Tania has submitted her body to conscious transformations to achieve that opacity that distorts her age. Her corporal forms and shaved head blur all relationship with the sexual appeal models western culture has created throughout time. “The feminine body is supposedly the paradigm of beauty in art and my body is not beautiful nor is it perfect. It does not match the contemporary canon. It is closer to the Venus of Willendorf.” In this similarity with prehistoric figures, Tania’s work seems to open another potential reflection field on a relationship with notions of a mythic understanding of primitive pieces which made her an early disciple of Juan Francisco Elso and an admirer of Ana Mendieta. In this sense, Tania Bruguera does not ignore the valuable contribution of these two builders of new mythologies who took, especially Ana, a not at all simple path of self-exploration. Perhaps, like her, she discovered that “nakedness was an important resource for the issue of femininity. The naked woman is facing you saying things to you and making you face things she wants to say to you… You have no defense at all; all your defects are outside; you are in the vulnerability of ridicule.”

But Tania – as Mendieta before her – is not unaware of how to assume it with some rituality and an ethical, not necessarily religious, basis: “I believe that energy may come from nature and that people codify it in a given way… I believe organized and classified religions have to do more with power than with religiosity…” In a piece like El peso de la culpa II (The Weight of Guilt II), Tania – kneeling on the floor with the head of a lamb before her – covers her hands with lamb fat and leaves her greasy marks on the floor, just as Ana Mendieta did with blood on the wall. In this gesture, the artist is loaded with new powers.

Tania Bruguera’ artistic space is her hiding place and her captivity. “I am a captive of art because I cannot express myself in any other way.” When she was twelve she began to study at the Elementary School and, since then, art has been for her a “system of thought.” Today she cannot escape it and she creates her silent space of isolation. Lo que me corresponde (What Belongs to Me), a 1995 piece, was a foam rubber rook in which many eyes replaced the buttons on the padded walls. The impression the spectator received was that of a mental hospital. It was “exceedingly maddening,” Tania told me. “There was a couch and a trunk with a metronome. Lights were zenithal. People were shut away there for a time they were unable to control.” Also “the place, entirely covered with meat, offers the idea of an inner madhouse, as if looking at yourself from the inside, as if I were inside a person.” In El cuerpo del silencio (The Body of Silence), the subject of the work provides a very evident protected space and a hiding place for self-flagellation.

In Tania Bruguera’s oeuvre, space is inseparable from her proposals and of a very much achieved effect in correspondence with the concentration it requires as a communication channel. “I like to create an environment in which people can be nearer to what I am doing, because art is like creating a world.” Preferably closed spaces without defined paths for the audience create an expectation for inner transit in works in which they can enter. In more hermetical works, the artist seems to build a hiding place for herself where solitude and nakedness place the spectators in a transgressive position of privacy and silence. Startlement is part of the desired effect, while the artist does not seem to notice that the audience is there and that it is like a viewfinder eye or a spy. They both share the circumstance of that space magnetized by air.

In other cases, when the artist moves from one place to another and does it with the attitude of someone “trying to reach some place,” it seems to show the permanent state of unease every human being has. This is what happens in Destierro (Exile). Entirely covered with earth and nails, the artist leaves the legitimized space and walks among the people, in the streets, in the midst of an evident confusion. This work would seem to be a tribute to Juan Francisco Elso when transmuting in a real and humanized scale those clay and earth sculptural bodies the artist loaded with energies and pierced with darts.

The language is an expository speech in the pieces: silence and solitude are essential metaphors. Although there may be other people in the works, which is not frequent, the protagonist is always in the artist’s alter ego and precisely in that solitude it finds all the expressive possibilities which demand a participating complicity from the audience. Language, because of the reticence of some resources, may at times be monotonous and makes one think that repetition is also part of a visual behavior based on an obsessive redundancy that may be in a position to lacerate the artistic result. The artist uses it intentionally, but when pretending “the spectator not to see the work, but live it” it is evident that it may be exhausting to repeatedly live similar situations with the same intensity. The implication of spectators has one of its main resources in the serenity of the artistic action: “when you see things as aggressive, as grotesque, as difficult to do, equanimity creates a great contrast. It is an impact element.” The artist uses it convinced of its effects. In serenity she locates a sort of social behavior. “Although the worst thing may be happening, this serenity has to do with a general behavior… perhaps this is its more Cuban trait… the human response to an adverse situation.”

Contrary to the visual resources used by Ana Mendieta and Juan Francisco Elso in their most acknowledged works, what interests Tania the most is not the plants or the natural environment. Her approach to telluric elements coincides with them in that conscious appropriation of the cosmic energies in air, water, earth and fire, understood as protective and evil forces which may be apprehended and manipulated. Animals in their more grotesque states – raw meat, blood, fat – or in their most humble image, “the lamb”, an attribute of so many powers derived from its identification with God, with its humility and sacrifice. The manipulation of lambs in Tania Bruguera might be understood as a strategy of power, since lambs are defenseless animals that are still sucking, dependent and meek, but that according to an old saying, in their meekness they do what they want (I’m meek as a lamb while doing what I want), which makes one think in a strategy of simulation and irony, all in all another form of hiding in that apparent naïveté of “saying without saying” that can be found in Tania’s work, who when speaking of lambs says that although “they are the symbol par excellence of submission, I could verify they are not submissive at all. When I used them in the performance they did not want to walk. If you hit them from behind they do, but if you hit them from before they are exceedingly rebellious. Their image is associated with submission, nobility and goodness… but submission is a way of dying.” Tania’s oeuvre always seems to be building “bridges between life and death… and talks of an inner conflict that goes beyond the relationship between art and society.”3

Tania uses traditional sayings as titles and topics of many of her artistic works and she knows that her pieces – because of being ephemeral – live and transcend orally; this documentation of the art event is very interesting and considerably differs from the way Ana Mendieta worked, since they move from a system of visual referents to another and in the transit they change from being an image to becoming a legend: “works remain as words, a rumor as a way of existence of the piece. That interests me very much.”

Tania does not abandon her permanent utopia because “I belong to the generation in which Che was a paradigm… art is for me a great weight I carry… I would like to be a good human being.” Tania and her alter ego are ready to make the next performance after a total fast to reach the piece and the audience in a purifying asepsis. Like the Taino shaman in the cohoba rite, Tania takes on the work with an effect of ethical and spiritual cleanliness. As then, the apparent immobility of time offers the artistic space a mythical dimension. Tania’s fears pigeonholings and classifications of her work, her concerns about the manipulated interpretations that may be made from it. Her worry to have her work systematized and seen as academic makes her think in searching new paths. “I feel I have to do something different.” Tania is in a moment of reunion, but she anticipates nothing: she always prefers the adventure of silence.

1 All the quotes of the artist are from a conversation held for this article in August 2000.

2 This is the Cuban Adjustment Law enacted by the United States government which encourages illegal emigration.

3 Juan Antonio Molina, “Entre la ida y el regreso. La experiencia del otro en la memoria” Catalogue for the exhibition Lagrimas de Tránsito (Transit Tears), Wifredo Lam, Havana, 1996.