Juan Antonio Molina

October 1996

From: Molina, Juan Antonio. “Entre la ida y el regreso: La experiencia del otro en la memoria”, 23 Bienal de Sao Paulo (Brochure), Consejo de las Artes Plásticas, La Habana, Cuba, 1996 (illust.) pp. 1 – 4.

__________________________. “Entre la ida y el regreso: La experiencia del otro en la memoria” Molina, Juan Antonio: Revista de arte Cubano, Ruta Crítica. No. 1/1997. (illust.) pp. 68 – 70.

Between Coming and Going: The Experience of the Other in the Memory

by Juan Antonio Molina

Tania Bruguera’s work is marked by the experience of the other. She takes on art as a functional and spiritual splitting. Through that splitting she puts herself to the test in various successive roles: quoting, appropriating and bringing to conclusion the work of another artist; taking on extra-artistic functions, also unfinished (or not made) in a social level; making a work reproducing historical processes and circumstances, relatively alien to her individual experience, and concentrating in the object itself and its communicational possibilities. The first case is illustrated in the exhibition she made in 1992 as a tribute to Ana Mendieta’s work. In it, Tania repeated some of Ana’s works, including a performance, and showed pictures of some sculptures by the other artist. Her identification with Ana Mendieta’s spirit reached a point that, since then, critics agreed to classify Tania as a mystic artist, focused on the search for the religious essences of creation, a sort of union of author and work to propitiate an “Eucharistic” consumption of the work of art by the spectator. What she was actually interested at the time was in establishing a cognitive relationship with Mendieta’s work, feeling the aesthetic experience of the other, entering into a zone that was not stylistic, but personal, biographical, intimate.

The problem is that Tania’s work has always had to do with death and with the transcendence of a memory. In her appropriation of Mendieta’s experience, Tania was offering her own memory as an area where the artist who had died in 1985 would transcend. She made a reconstruction of Ana’s work, which at the same time was a reconstruction of Ana’s profile in Tania’s memory and in the “esthetic memory” of contemporary Cuban art.

When Tania defines her work as an experimentation of the various functions of art, she is actually making reference to the various functions of Cuban art, functions that are part of an “esthetic memory” she reconstructs little by little. Her newspaper Memoria de la postguerra (Postwar Memory) was a work intended to restructure that memory, not exactly because of what it meant as a graphic document, bur as a sociological gesture in itself. As a gesture, the newspaper-performance was a reconstruction of the esthetics that started to develop in the ‘80s and that are an important part of present Cuban art.

Everything that took place around that work had been foreseen: it was part of the gesture. The gesture was not unfinished, that is why Memoria de la Postguerra is not a frustrated work, but simply a work that includes frustration among its functional premises. The name of the newspaper covers the entire Tania’s esthetics. Her work has constantly been a remembrance of something, an evocation presented as a creative process. The importance she grants to performances as the structure of her work has to do with considering art a process and not a result materialized in an object, but the course through which something transcends itself. Objects are concentrated in time more than in space. She herself, when acting, is usually motionless, being there more than acting. That is how the visitors to the 5th Havana Biennial saw her lying for two hours in a useless boat. And that was how she was seen in her most recent performance, hanging from the ceiling of the gallery as just one more piece in her installation.

The Havana Biennial works were all of a funerary nature. Tania was sleeping in the boat, but could have been dead. The boat could have been a coffin, unearthed (banished?), kept afloat and placed in a non-place, in that limbo between coming and going. What she was offering was the sight of death, of solitude and of time going by. In another of her installations, with Tabla de salvación (Salvation Board) as a title, several sheets of black marble were supported between wooden structures like the ribs of a ship. The pieces of marble clearly functioned like monuments to those who had died trying to cross the Florida Strait. Once more Tania approached the experience of the life and death of others and found in her memory the references she had to devise evidence of the unknown and, at the same time, intuited. The paper bags in the third installation – with El viaje (The Trip) as its title – also seemed to be evidence of a shipwreck more than of a landing. All these works made up one single speech summarizing the trend in present Cuban art towards what is documentary and archeological, in what I have given the name of “pragmatic esthetics” because of its capacity of projecting as a sign, what the Stoics called pragma, that is, the objective universe which makes up the referent of the sign.

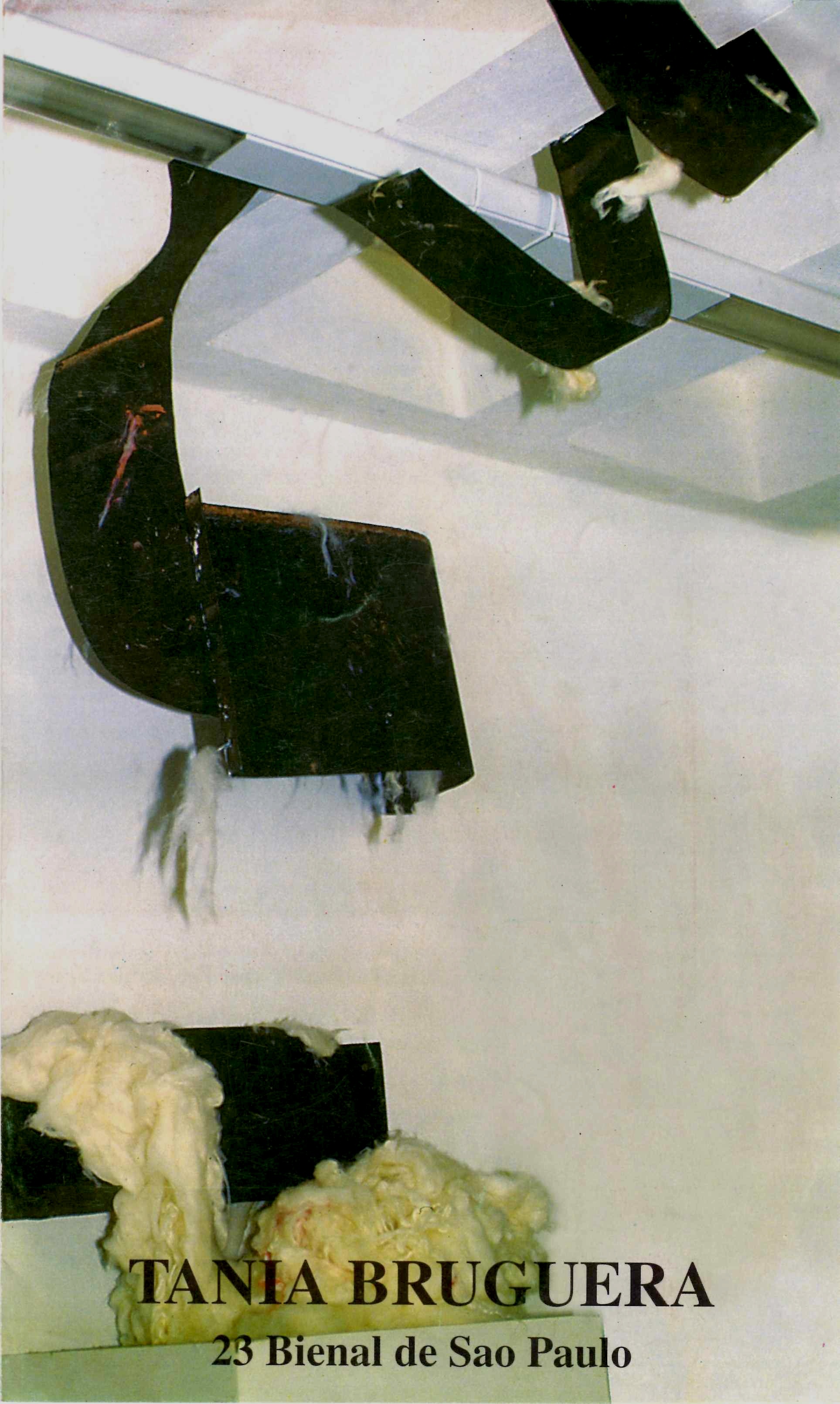

But in Tania Bruguera’s work even what is pragmatic functions as an allegory. If in those 1994 installations what is heavy, what sinks, what is wrecked, was linked with death, in Dédalo o el imperio de salvación (Daedalus or the Empire of Salvation – 1995) what is light, what flies, what takes off, is linked to life. But this is an illusion. Birds are the verification of utopia and its impossibility. With Tania’s art as a basis, we may understand life as a break out, an escape, a feeling of weightlessness. Death would be reaching the bottom and becoming the slime of memory. To live (to fly) is also to escape from memory, to enter the land of oblivion. But this flight is almost impossible. Tania’s birds are therefore heavier and heavier, more carnal, more anthropological. They are not made for flying, but for dying. This image summarizes her performance. Tania floating between heaven and earth does not fly, neither does she lie, but her disposition is to fall dragged by the weight of her own bleeding heart.

The dedication and sacrifice this image implies are for Tania the duty of art. The actual function of what is artistic would be in that bridge between life and death, between freedom and weightlessness, between oblivion and memory.

The environments she is now creating are a reconstruction of the artist’s vital space, the signals of precariousness, violence, repression, vigilance and death in this space speak of her inner conflict, which goes much further than the relationship between artist and society.