Title: Autobiography (Version inside Cuba)

Year: 2003

Medium: Sound installation

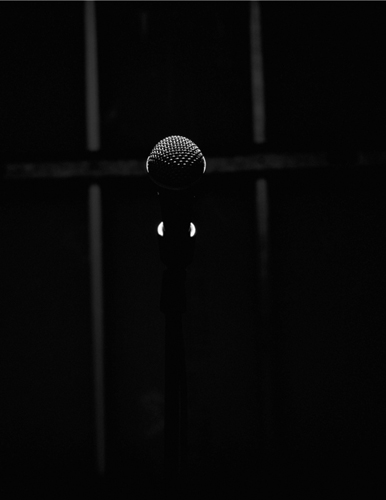

Materials: Unpainted space, two Soviet loudspeakers from the ‘70s, egg trays, a wooden stadium, 16 subwoofers, a switched-off mike, three unfinished rock walls, an electric bulb

Dimensions: 65.6′ x 49.2′ x 16.4′

Statement

Autobiography is a piece in two versions, one to be staged in Cuba and another to be staged abroad. In both of them the audience has an auditory experience that becomes physical. The concept of sound is used as an independent and self-sufficient means capable of creating images in the conscience of the individual. The visualization the work evokes emerges from the memory and knowledge by the spectator on the experience of the Cuban Revolution process. It is the spectator who preserves the images of the collective emotional memory.

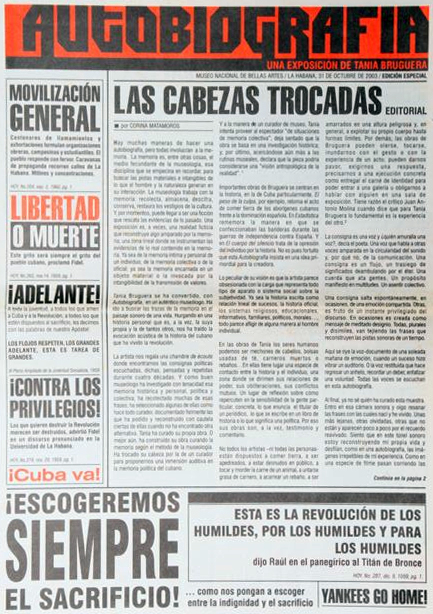

Autobiography(Version inside Cuba) was held in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Museum) in Cuba during the 8th Havana Biennial (2003). In the white unpainted space there are still some residues of a former exhibition (holes on the wall, marks of paintings that were hung there and so on). Two Soviet loudspeakers are placed at both sides, a dais in the center framed by three sides with unfinished plasterboard walls. There is a microphone standing on the dais. The glass walls at the entrance are covered with egg trays to muffle the sound outside so as to create a shock effect when entering the space and experiencing a sudden change from silence to the sound coming from the loudspeakers at a high volume. From the installation, comes the sound of reiterated slogans from the repertoire used by the Cuban Revolution in its political propaganda: “Fatherland or Death!” “Victory Forever!” and others. But some of these endlessly and passionately repeated slogans have lost a context justifying them. The audience may go up the dais and use the mike. Then they will notice(because of some subwoofers placed under the dais) the vibrations of the slogans coming from the loudspeakers running up their legs. The mike does not work although it seems to be connected with the amplification equipment that the security guard in the hall keeps in a gesture of apparent control.

The work appeals to the conscience and functions as an autobiography not only of the artist, but of all Cubans born in the revolution who recognize the rhetoric of political oratory, in this case slogans issued by the power which are part of their social reality and have entered their conscience as individuals. These are revolutionary slogans audiences (foreign as well national) are identified with or alien from depending on their knowledge of the Cuban revolutionary context. While in other places the passage of time is measured through fashion and music, in Cuba it may be measured by the withdrawal or insertion of some revolutionary slogans. The work shows how in the life of Cubans, merged with the political process, there is no clear distinction between public and private facets of individual existence to contribute to the needs of the macro-social project. The work creates a moving and critical encounter with Cuban history in the last 50 years.

Exhibited

| 2012 | |

|

Schlagwörter und Sprachgewalten. Wie in der Sprache Macht und Identität verhandelt werden. Kunsthaus Baselland, Muttenz, Switzerland. Curated by Nadia Schneider Willen. September 15 – November 11 |

|

| 2010 | |

|

Tania Bruguera: On the political Imaginary (Survey Show). Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York. Purchase New York, United States. Curated by Helaine Posner. (catalog) January 28 – April 11 |

|

| 2008 | |

|

No es neutral. Tabakalera, Centro Internacional de Cultura Contemporánea. Donostia, San Sebastián, Spain. Curated by Daros Latinoamerica. Julio 19 – October 5 |

|

| 2006 | |

|

Noticias del Filibustero. Part of the Event “Estrecho Dudoso” (Doubtful Strait). Museo de Formas, Espacios y Sonidos, San José, Costa Rica. Curated by Virginia Pérez Ratton and Tamara Bringas. December 01, 2006 – February 15, 2007 |

|

| 2004 | |

|

Art Projects. –Autobiografía (version inside Cuba)-.Art Basel Miami Beach 2004. Rhona Hoffman Gallery. Miami, United States. June 16 – June 21 |

|

| 2003 | |

|

Autobiography (inside Cuba.) National Fine Arts Museum, 8th. Havana Biennial. Havana, Cuba. Curated by Corina Matamoros. November 1 – December 15 |

Documentation

Scrolldown for IMAGES

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|||||

Autobiography (inside Cuba)

National Museum of Fine Arts, Havana, Cuba

photos: Ricardo G. Elías

Selected bibliography

(by alphabetical order)

Antón Castillo, Héctor “El ‘arte útil’ de Tania Bruguera,” Arte Cubano, Otros Espacios, no. 2 / 08, Havana, Cuba, 2008, (illust.)

_______________________ “El ‘arte útil’ de Tania Bruguera,” Salon Kritik, September 25, 2008.

_______________________ “El ‘arte útil’ de Tania Bruguera,” blog Penúltimos Días. September 16, 2008.

Cippitelli, Lucrezia “To put an end to aesthetic judgments. Life, useful art, civil society and the diasporic gaze,” Tania Bruguera, On the occasion of the solo show “Giordano Bruno for Saint,” MLAC – Museo Laboratorio Di Arte Contemporanea, Rome, Italy. Ed. Postmedia Srl. Fiesola, Italy, November 2010, (cover & illust.) pp. 16 – 31. ISBN 88-7490-051-0

Negrín, Javier “A platform,” Gaceta de Cuba, Visual Arts Section, January-February, 2004. Havana, Cuba.

Smith, Terry “What is Contemporary Art?” Part IV Countercurrents: South / North, chapter 9 The Postcolonial Turn,” Ed. University of Chicago. Chicago, United States (illust.) pp. 163 – 165. ISBN: 9780226764313

Quotes

“(…) The title, Autobiografía (Autobiography), intended to point out how the entire life of the artist, or rather of the Cuban individual, has been amalgamated with a political process of which the platform is a good symbol, how private and public aspects of her existence get mislaid, urged by the needs of the macro-social project (oratory needs, in this case, of a political auto-da-fe). Perhaps because of that peculiar amalgam, when the artist invites the audience to interact with the piece using a mike on the platform, she mentions that with her action she will revive moments of her individual past, as if the slogans were a sort of “acoustic fairy cake” to activate affective memory. At least in the case of the curator it worked, judging by the words with which she accompanied the show…”

Javier Negrín “Una Tribuna”, Gaceta de Cuba, January-February, 2004.

“…The following year Tania Bruguera was invited to exhibit at the National Museum of Fine Arts as part of the collateral samples of the 8th Havana Biennial (2003). This time she was able to accomplish an idea in which the spectator could walk on an echo dais. Revolutionary slogans entered and left the memory depending on the degree of identification or estrangement the audience (whether foreign or national) experienced when feeling the vibrations under their feet. Autobiography is a false theater piece. It takes us back to a textual evocation of the rallies or marches of the imaginary of the Revolution as a performance art. The only concrete thing in it was a mike on a wooden surface marked by the feet of the people. But the sound of patriotic words diluted inside the dais until it transformed into that buzzing of history backing us with its invisibility…”

Héctor Antón Castillo, . “El ‘arte útil’ de Tania Bruguera,” (“Tania Bruguera’s ‘useful art'”) Arte Cubano, Salon Kritik and blog Penúltimos Días. September, 2008.

“(…) The same mechanism was used in Autobiografía, presented at the 8th Biennial in 2003, in the form of a sound installation. During which the spectators found themselves being engulfed by slogans of the Cuban Revolution, diffused at a high volume by two loudspeakers. The same work then took the form of a CD, produced under the collective name Las Chancletas Vanguardistas (…)”

Lucrezia Cippitelli, “To put an end to aesthetic judgments. Life, useful art, civil society and the diasporic gaze” November, 2010.

“(…)was the main one to be shown in the temporary exhibition space of the Museo Nacional devoted to Cuban Art. This was a bold and brave gesture by all concerned. The large space was void of all but two speakers at either end, and a platform at its center, on which a microphone stood, framed on three sides by a curving wall. All this was made with the rawest of materials: cardboard, packing cases, palette planks, and the like. So und was vividly present, as surging slogans, the calls to arms of the Cuban Revolution, above all such oft-repeated phrases as “Libertad o Muerte!” “Hasta la Victoria Siempre!,” and “Viva Fidel!” Most of the time, however, these were scarcely distinguishable. But careful listening – especially if you stepped up to the microphone – disclosed their rhythmic power, their relentless presence, their selection of willing subjects, their shaping of crowds, their womb-like comfort, their obliterative omniscience, and their falling short -a landscape of memory of what it must have felt like, within the body, in the mind’s ear, to grow up during the revolution. Visitors were invited to record their own slogans, statements, or speech of any kind, which were then added to the mix. The implication here is that the voices of the people might eventually drown out those of the ones who claim to speak for them. Or perhaps not(…)”

Terry Smith “What is Contemporary Art? The Postcolonial Turn” (144) London, 2010.

“(…)Autobiografia echoed, and in a sense completed, an earlier work of art, a painting by Antonia Eiríz exhibited in the historical survey of Cuban art at the Museo Nacional. in 1969 Eiríz made Una tribuna para la paz democrática, a large vertical painting that locates the spectator as the speaker about to step up to the microphones on the speaker’s stan at La Plaza de la Revolución. The stand is black, the barricades around the square are red, as are the waving flags, – actual flags, pasted into the painting. But the crowd is an undulating mass of surging gray and white marks, shapeless, ominously empty – waiting to be formed, or forever formless? In a similar way, Bruguera puts us, alone yet in public, alone yet with countless others, into that same space. With the difference that, in her installation, the barricades are down. Formlessness is all around. But the state, we plainly hear, can take form at any time. Which form it takes depends, partly (but which part?) on us(…)”

Terry Smith “What is Contemporary Art? The Postcolonial Turn” (144) London, 2010.