with Michelle Chen

11.10.2012

From: Chen, Michelle. “You Define the Space,” Culturestr/ke, , New York, United States(illust.)

http://culturestrike.net/you-define-the-space

You Define the Space

with Michelle Chen

Tania Bruguera is no stranger to controversy, but then again, she has made a career out of being a stranger of sorts. The Cuban emigré has been known for cerebral installation works that play with themes of contemporary history and political memory, and has alternately examined and immersed herself in forms that reflect activist culture and ideology. Around this time two years ago, she was presenting “participative mural painting” involving propaganda graphics and bricks artfully arranged around smashed glass planes, to depict a simultaneous effort to launch a general strike in Spain. She’s also recently ventured south of the border to launch an (artistically inspired) political party for migrants in the Mexican elections-a direct action for which she is half organizer, half provocateur. These days, she’s helping immigrant youth with their paperwork and holding artist meet-ups in Queens.

Over the past year Bruguera has stepped delicately over the edge she’s long straddled as an artist-the cusp of observer and participant-and pivoted from art to action by creating an organization that serves and represents immigrants. In the process of building Immigrant Movement International (on a minimal budget), she’s turned an office space in Corona into a physical embodiment of aesthetic vision and social action, carving out a space for herself as an artist running a grassroots service center amid a symphonic pastiche of migrant cultures. She recently spoke with CultureStrike editor Michelle Chen on the work in progress at Immigrant Movement International, and her next directions.

Describe where you are right now-the space in Corona and what it represents.

We are at the Headquarters of Immigrant Movement International. We are located in front of a lumberyard hardware store, next to one of the biggest supermarkets around here and next to the 7 train station. We are at an intersection with high circulation and a natural path for a lot of people living around here to find our space. This is a place where many things happen in one day; it is a flexible space with an understanding of the complexities of what it is to be an immigrant. We hope to be a suitable environment where each person can fully develop their capacities as engaged participants in society.

We try to work with different demographics in our community, which is visible throughout each day’s events. Normally, our days start with the stay-at-home moms who come for a health workshop that includes not only physical exercises, but also workshops on identity, on domestic violence, on stress, on gardening and health eating, and on how to understand children’s behavior. “Health” meaning a better understanding and managing of the mind and body and the ecology of interaction. A little later, a group from the Asian community comes to take Spanish classes as a second language (we should say as a third or fourth language in some cases). After that we could have an artist in residence at the Queens Museum of Art working on a proposal for Corona Plaza, a new public space for the community. Then we have the youth orchestra project with the kids. After that, we can have the computer class or the citizenship class, and by the evening we have either a cinema club or a traditional dance group from Latin America or legal intakes. We open at 8:30 am and we close at 11pm or later. Our programming involves a collaboration with other community organizations and groups.

After one year of giving services to the community, we have decided to formalize them into a structure that is recognizable as an educational project-a school, a holistic education. We are planning to open in January of 2013 a school for immigrants by immigrants, which combines practical knowledge with creative knowledge.

So, this would be a school within the New York City Public School System?

No, it would be an alternative school for the moment. I really would prefer the beginning to be independent and to work with the good side of institutionalization, but not with the bad side.

We want to have the freedom and flexibility [brought on by an] understanding of what is needed when it is needed. By not having a standardized system, we want to respond more to the people in the project than to the idea of an institution. It will be a project where people are not an anonymous bunch but individuals with values and with something to give back of equal importance to the rest of the group.

How do you envision that happening? Do you think that one day you will be fully supported by the members, or something like that? How will it become a sustainable thing?

The immigrant community has all the resources you would need to do anything you want. Immigrants are part of all the jobs you can think of; they are prepared and they are eager to contribute not only to their community but to society in general. This will be an effective way to value the knowledge each person can provide. Don’t forget that members of our community may have had a high-skilled job in their countries of origin, and here their knowledge may not be in use; that they had great political training that here is not activated; or that they have a work ethic that here is not completely appreciated. Just to give you some examples. We can learn from immigrants so much! The mistake is to see education in terms of re-education and assimilation. We want to see it as an exchange of multiple knowledges and multiple perspectives.

In terms of sustainability, at some point we discussed the idea of filing for 501(c)(3) status, but we decided not to. These entities are born with the limitation that they can not intervene directly in politics, and the grants they can receive sometimes come with a great deal of restrictions and, for sure, an ideology, that sometimes is the same [as yours], but sometimes [requires your] bending your position a bit and orienting the work in certain directions.

[And in terms of building a sustainable membership structure], at the same time, the people who are working here-they’re struggling economically. We decided to start in January a membership system where you give one day a year (24 hours) in services, as a trade system, which would also build a sense of belonging and ownership of the project.

Is this the project that takes up most of your time now? Are you able to take on other artistic projects? Because this is so different from the work you have done previously: Do you ever miss being in the studio, having exhibits, and being more of an independent artist, rather than having this whole organizational structure that you need to take care of?

A big, complicated thing I am dealing with right now is that on one side, I feel like it’s too easy to do that kind of artwork, so it’s not challenging enough. I know how to do it. I know what the reactions will be. I mean, you cannot control everything, but I have a pretty good idea. And it doesn’t satisfy me that much. Why? Because I don’t like anymore this kind of semi-passive attitude from the audience. To me, that’s not interesting anymore as art. You know what I mean? Because it’s too close to what could be entertainment, even if you’re talking about political issues. What I want to do is art that-when you are in it-you can’t separate from your everyday life.

A project like Immigrant Movement International is a lifelong one and it needs to have all your energy, all your awareness and all your ideas focused on it. Art is a component of it, specifically what I call “arte útil” or useful art. The first year and a half, I could not do anything else; it was a completely consuming experience. I went in immersing myself in the more political aspect of it, and now I’m trying to reconcile it with creative values as a political force. What artists do is to not only imagine a different world but to go and try to create it.

I do not miss the Studio; I’m in the Studio everyday, [only] now we are a collective and the energy of the place and the conception of the program are the materials we are working with. It is true that having an organizational structure is heavy but it is also very gratifying working with other people towards the same goal and having people bringing a vision and ideas beyond your dreams. While I value the various degrees of intensity art-exhibit formats have, I really enjoy the freedom to work within our own set of rules. I enjoy art that is part of life, not apart from life.

One advantage the art world has is to create connections between things, and one is the possibility to operate at an international level with very specific and local issues that are interconnected with other specific and local issues in another part of the world.

The idea is to do a project that is interesting for politicians as well as for artists; to take the best out of each world.

A lot of people looking from the outside may find it a bit odd that an artist who is used to doing these extensive, really conceptual installation pieces would throw herself into the life of an undocumented immigrant for a year. So, can you maybe explain where you see the intersection between art and constructing your own new reality?

First of all, the [idea of] being an immigrant for a year is a spin done by the first article we had,which appeared in The New York Times, when the project had only [been ongoing for] a few weeks. The writer never understood what performance art is and on top of that saw the idea of living in a multifamily apartment as a social experiment, instead of what I could afford with my minimum-wage salary. I was very lucky to live with the families I lived with, who are still friends after we all had to move. (The landlord wanted to evict us to increase the rent, and we all dispersed to various apartments.)

The criticism that goes on in the art world, to some degree, kind of dwells in its self-contained universe. Whereas in the activist world, you’re dealing with real people and communities. The stakes are higher, things have consequences, and you have to be careful. Failure is not an option; a mistake can mean that someone is deported, a family separated. I felt like as an artist, the best thing I can do is be a better citizen.

Do you see the same relationship between art and politics in your other project, the Migrant People’s Party that you founded in Mexico? Which was also sort of a political action, but in some ways, it was also an artistic project and it also had to do with form and symbolism.

Politics have their points of contact at an international level, but they are locally implemented, so each place where the project emerges has to respond to the specificity of politics of that place, and to the political history.

Another question, about your project and tribute to Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta: do you see a connection between that work and your current activist work now, because she was an artist who was a migrant herself, and that was how she engaged both her art and her politics?

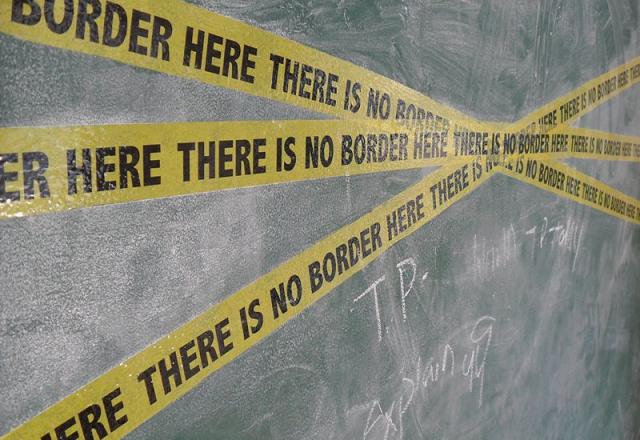

First of all, that project makes me feel so old. I did it when I was eighteen. I have to be honest, I didn’t think about it in the beginning. But, it has a lot to do with it, not only because it’s a long term project, but because Ana Mendieta was an immigrant herself and I have worked with her figure from the inside of Cuba-like questioning what is belonging? What is territory? What is country? And all that stuff. Now, I’m asking myself the same questions, but not regarding Cuba. Regarding yourself. Not the way in which the space defines you, but the way in which you define the space.